You have to be very brave to ask for help, you know?

But you have to be even braver to accept it.

Los besos en el pan (Kisses on the Bread). Almudena Grandes

Years ago, I participated in a theatrical workshop, which, they said, was imparted by an important mime. I regret not remembering his name. The workshop was conducted for students in the theater group at the center where I studied. From that workshop many years ago, I only recall one activity: The exercise of asking.

The activity involved one person asking another for something, anything from a kiss, a hug, or a cuddle to a pen… The person asked to provide what was requested had previously devised a code: a specific action or task that the requester had to perform to receive what they had requested. This could include giving the person asked a hug, touching their ear, or tying their shoelaces, for example. At times, the person asked demanded simple things, while other times, their requests were more challenging to decipher, but never impossible. The request was only achieved if the requester knew what she had to do: the code.

.

Carlos Saura, Niños pidiendo limosna (Children Asking for Alms). 1950s Spain

Carlos Saura, Niños pidiendo limosna (Children Asking for Alms). 1950s Spain

To do this, the person asked gave clues: looks, phrases, smiles… The requester had to be vigilant, observe the person closely, find them, and notice any subtle movements that could guide them toward their objective. They relied on listening and their intuition to discern the clues provided. That’s what was the Exercise of Asking consisted of.

REQUESTER: I want your pen.

PERSON ASKED: (Thinks) If they want me to give it to them, they need to caress my face.

REQUESTER: (Acts) Searches, asks, improvises, listens to what the person asked needs, or tries to figure out how to convince them.

PERSON ASKED: (Acts) Gives clues showing their face, smiles as they caress their hand…

REQUESTER: (Acts) Caresses the face of the person asked.

PERSON ASKED: Here’s the pen.

Many people got what they had asked for quickly, either because the person asked had a simple code or they were adept at interpreting signals. Others, myself included, took much longer and walked in circles around the person asked. We repeated movements, touched, talked, offered things… all without receiving anything in return or finding something unexpected we hadn’t asked for.

And I remember this exercise because it has helped me in real-life situations where I’ve had to request and obtain something. It taught me to look, observe, smile at the other person, and offer what I have until they provide what I’m seeking. Other times, I have been the one who has had something that others wanted. I’ve always given lots of clues.

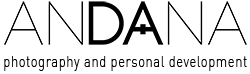

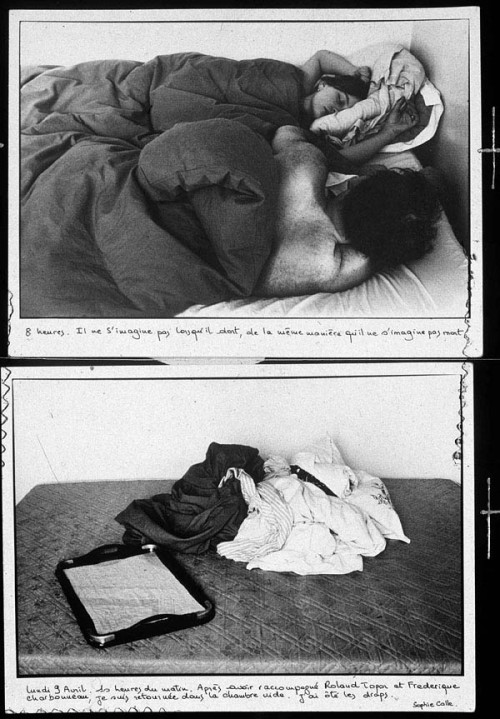

Sophie Calle. Los durmientes (The Sleepers)

Sophie Calle. Los durmientes (The Sleepers)

.

Related to the exercise of asking in photography, I imagine Sophie Calle when she wanted to develop her project Los durmientes (The Sleepers). For a few days, she devoted herself to calling strangers to sleep in her bed that night. What would she say to convince them that she was not a serial killer and that their sleep would be part of art history?

«I asked some people to give me a few hours of sleep. ‘Come to sleep on my bed. Let yourself be photographed. Answer a few questions.’ I proposed a stay of approximately eight hours each, similar to a normal night’s sleep. I contacted 45 people by phone: strangers whose names had been suggested to me by ordinary acquaintances, friends, and neighbors. I called them to ask them to come sleep during the day (…) My room had to be constantly occupied for 8 days, with sleepers rotating at regular intervals. (…) The occupation of the bed began on April 1, 1979, at 5:00 p.m. and concluded on Monday, April 9, 1979, at 10:00 a.m., with a total of 28 sleepers taking turns. Some overlapped (…) A clean set of sheets was at their disposal (…) It was not a question of knowing, of surveying, but of establishing a neutral and distant contact. I took pictures every hour. I watched my guests sleeping.»

«What I enjoyed was having in my bed people I didn’t know, strangers from the street. I was unaware of what they did. Still, they entrusted me with their most intimate selves. (…) I observed them as they slept for eight hours at night, their movements, whether they spoke, and if they smiled. These people did not know who I was or what I did…»

Sophie Calle

And how did Spencer Tunick convince us, more than 7000 people, to pose nude in different positions in Barcelona?

We often don’t need to ask for help; others ask it of us. This is what happened to the artist Ana Palacios. She mentions that her first photographic projects originated when she chose to travel and work for a non-governmental organization. They said all they needed of her was to use her camera to convey what she witnessed to the world.

Since then, Ana’s projects have offered visibility, knowledge, and potential resources. Her projects promote equal opportunities, change, and improve the world by simply asking to be present and look.

Ana Palacios. Albino. Tanzania

Many photographic projects require doing the exercise of asking because we often rely on others to fulfill our desires, and significant challenges can be overcome through trust.

Who hasn’t asked for a portrait when strolling the streets of their own city or on a trip? At first, it may feel somewhat embarrassing, but with time, you realize we all appreciate being looked at, hearing, and helping. Asking becomes an act of bravery, demonstrating resilience, vitality, and strength.

We may confront ourselves and offer our many resources from a place of loneliness. Still, if we set aside our pride, shame, or fear of rejection, we can tap into the universal resources available to us, those offered by fellow human beings inhabiting our surroundings.

Perhaps this exercise of asking allows us to admire people who persist in pursuing what they desire, even when it may seem impossible at times.Ask. It’s time to start your project.

If you want to learn more about photography and personal development, I invite you to learn more about: