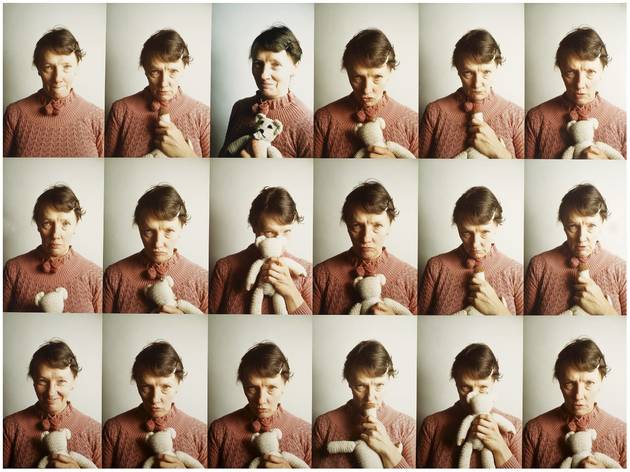

Photography is linked to concepts such as «recovery» and «empowerment» for people with mental illnesses, going hand in hand with its great potential as an occupational activity and catalyst for the construction of personal narratives.

Martinez Azumendi

This article follows up on The Origin of Photography as a Tool in Mental Health. Part One.

In this second part, we jump to the 20th century. Photography as a therapeutic tool has been used and researched by many doctors and psychiatrists through different techniques and both individual and group resources:

- Self-recognition and body self-image.

- Reactions and emotions expressed in response to images.

- Discussions.

- Projective purposes.

In 1973, Dr. Robert U. Akeret published Photoanalysis: How to Interpret the Hidden Psychological Meaning of Personal and Public Photographs. He pioneered the methodologies used today for working with family albums. Akeret’s method consists of reviewing the patients’ family photographs and asking them to determine their chronology based on content and technology, discover who was behind the camera, who kept the photographs, find evidence to interpret the relationships of the people depicted, and then test these hypotheses by asking the owner if they were true. A wonderful manual for intrafamily communication that broke pre-existing ideas, revealing emotional truths.

In the second half of the 1970s, photographer Jo Spence placed photography in an educational context; she referred to herself as an educational photographer. She used photography as a tool for visualizing, representing, and healing personal and social processes, and she was also a key artist in English photography from the 1970s onwards.

Self-image, psychodiagnosis, and early therapeutic approaches prove that photography is emerging as an accessible healing tool.

Since the 1980s, the works of David Krauss and Jerry Fryrear, pioneers in developing current strategies and resources in phototherapy for mental health, have been published.

Dr. Henán Kesselman o el Dr Cabau introduced a different approach, integrating Autobiography and Photographs throughout the therapeutic process.

We know that family photo albums usually capture the most relevant events in a family’s history, which means they carry a large volume of information that is significant and meaningful to each person within the family group.

It is necessary to note that Autobiographies and Photographs are personal documents. As such, they are privileged sources of information as they allow access to the history of the characters in a given context.

This is the task I assign when requesting photographic material: collect as many photos as you can that relate to your life. Once you have them, take some time alone to choose the ones that are meaningful, whether pleasant or unpleasant, that you think I should see. You don’t necessarily have to appear in all of them. The final number should not exceed 15. Pay attention to why you choose certain photos and reject others.

I also ask for individual photographic filiation, which consists of the following four pieces of information: The number of the photo (the first photo will be the one in which the patient was the youngest or not yet born. For example, a photograph showing their grandparents’ house), the age at which he was in each one, even if he does not appear, a title, and a brief comment on each photo. All this filiation must be recorded on a piece of paper attached to each particular photograph.

With this material provided, we now have the Exploratory Photo Strip or First Photo Series, which encompasses the physical spaces inhabited by the patient and their ancestors, open to being visually embodied through photography.

In her book Fotobiografía (Photobiography), Valencian psychologist Fina Sanz also describes a process of self-knowledge and personal development using family albums as a starting point for change.

“It is an approach that uniquely integrates the life story narrated and felt by each person, accompanied by images extracted from family albums, where the gazes of others intersect with our own and our own gazes with ourselves and the world around us.

Photobiography graphically shows us the social and cultural context we come from and the rituals and myths we participate in. It offers concrete images of the social values upheld by our ancestors and shows us how we positioned ourselves in our family environment and the changes we have made, evident in our bodies, faces, and gazes.

Photobiography is a guide for individuals to rediscover their past, learn to read the language of emotions in the portrayed bodies, and give voice to those silences and absences of pictures in certain periods of life.“

The accessibility and immediacy of images, their widespread use as a form of expression since early childhood, the integration of identity and personal aspects into artistic projects, as well as their role in providing support, expression, visibility, and personal exploration of physical or mental illnesses and emotional deficiencies, have led an increasing number of professionals to use photography as a means of improving the quality of life for individuals and communities.

While numerous international scientific studies support the use of Creative and Artistic Therapies for chronic patients, in Spain, these approaches are considered innovative, given the current healthcare infrastructure. Few national psychiatric centers implement them consistently and follow up over time. The article by Prefasi, S., Magal, T., Garde, F., and Jiménez, J.L., Uso del Arte y de la Creatividad en las Terapias Psicosociales (The Use of Art and Creativity in Psychosocial Therapies), published in Arte, Individuo y Sociedad (Art, Individual, and Society) in 2011, demonstrates how photography significantly improves the quality of life of chronic patients. It not only socially motivates them to communicate through the artistic field but also encourages them to use creativity as a weapon of social action. This is the document.

Table 4.

Relationship between the different chronic deficits experienced by the patient and the efforts made to overcome them through the photography course.

A magnificent tool that, having spanned over a century, embarks on its adolescence by joining participation and social work. After all, today, we all carry a camera with us. It’s time to share, exhibit, document, and explore.

But we don’t have to limit ourselves to hospitals or day centers; we all benefit from its accessibility. Photography becomes a tool for growth in infant and young environments, as well as for personal development and empowerment. It’s time to share this message with the world.

That concludes this fascinating story, which extends across many cities, projects, and health and personal development institutions. I’d gladly receive all your comments and contributions to this entry.

You can keep reading:

Photography as a tool for social integration