As a diagnostic tool for understanding mental disorders, different postures, attitudes, and phases (…), this part of the practical exam is perpetuated through photography.

Tomàs Dolsa i Ricart

Photography as a Therapeutic Tool in Mental Health—that’s the name of the article written by Óscar Martínez Azumendi and published in 2016 for issue nº 17 of the Atopos magazine. Mental health, community, and culture. He reveals the relationship between photography and psychiatry throughout history, which inspired the article you are reading. Download it here.

Oscar Martínez Azumendi, Doctor of Medicine and Surgery, specializing in psychiatry. Chief of the Mental Health Network of Vizcaya. He has served as the director of the Asociación Española de Neuropsiquiatría (Spanish Neuropsychiatry Association) journal. He is a member of the editorial board of various publications (Alternative Health International, Science, Discourse, and Mind, Norte de salud mental (Mental Health North), Rehabilitación psicosocial (Psychosocial Rehabilitation), etc.).

He is a professor in various university master’s programs with an extensive background in clinical research and service evaluation. He has a keen interest in the role of photography in the history of psychiatry, having curated exhibitions of a historical nature. He is the creator and author of the blog Images of Psychiatry at psiquifotos.com.

The beginning of photography in pathological environments may have been driven by the pioneer of psychopathology, Jean-Marie Charcot, in the Iconographie Photographique de la Salpêtrière.

Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) worked and taught at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, originally a saltpeter factory. The 19th century introduced humanitarian reforms in treating mental disabilities, and La Salpêtrière became a psychiatric hospital under Charcot’s administration. His research there attracted students and admirers from Europe, including the young Sigmund Freud.

Charcot became famous for his work in neuropathology through a series of lectures on hysteria, the first of which was given in June 1870. His method attempted to correlate observable signs of hysteria in patients with brain lesions discovered through an eventual autopsy. He aimed to provide an objective description of hysteria and epilepsy and their relationships, using the latest technology of the time: photography.

A total of 119 black-and-white images, mostly photolithographs, depict young patients in various stages of hysterical «fits.» These were complemented by medical records, including respiratory and pulse rates, extremely precise physical descriptions such as head and limb circumference measurements, and even transcriptions of the patients’ delusions.

The reproduced photographs are labeled according to the stages of the hysterical attack, as identified and named by Charcot:

![]() Période épileptoide, slide 13.

Période épileptoide, slide 13.

Presence of seizures, muscle contractions, or outbursts.

![]()

Actitudes pasionales-extase. Slide 23.

Passionate gestures, visible ecstasy, or withdrawal in contemplative or even beatific states.

![]() Béatitude. Slide 38.

Béatitude. Slide 38.

Although recognized as powerful tools, cameras have been restricted from psychiatric settings for significant reasons: to protect people’s privacy and to avoid shedding light on the abusive practices that occurred in these early institutions.

So, the use of photography in psychiatric environments was defined in two ways:

- By its content, usefulness, and purpose. Documentary, research, testimonial, or even protest photography.

- As a psychological tool for diagnosis or therapeutic purposes, whether occupational or as an expression of emotional content.

These early 19th-century experiences were based on physiognomic theories, describing mental illness based on appearance and representation. In the mid-20th century, the potential value of photography as a therapeutic and diagnostic tool became more widely recognized.

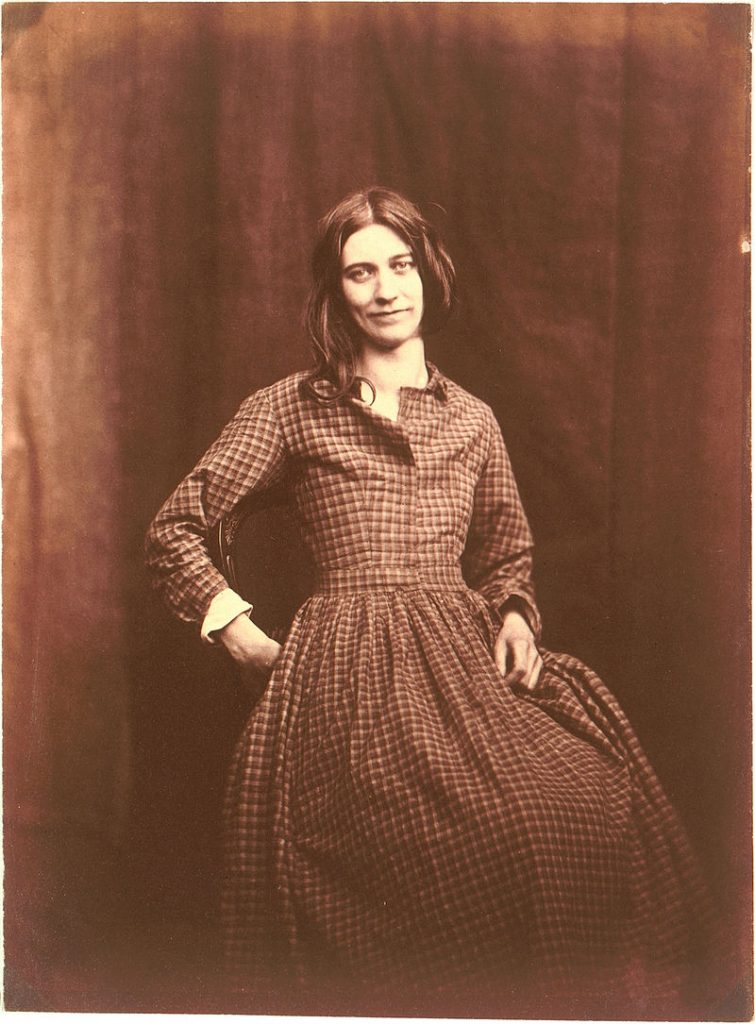

We can look at the work of Hugh Welch Diamond (1809-1886), known as the father of psychiatric photography, a physician, and a photography enthusiast. Between 1848 and 1858, while serving as the superintendent of the women’s department at the Surrey County Lunatic Asylum and basing his work on physiognomic theories, he photographed patients to illustrate different types of madness and define diagnoses based on the patients’ facial expressions.

In 1952, he held his first exhibition at the Society of Arts, titled Types of Madness. In 1856, he gave a lecture at the Royal Society describing the three roles of photography in mental health treatment:

- Recording external appearance.

- Identifying patients.

- Treating self-image. (Here’s when phototherapy is born).

But before Diamond, in 1849, Thomas Story Kirkbride (1809-1883), who was born the same year, used the predecessor to the cinematograph—the transparent photographs for the magic lantern—as part of the treatment, recreation, and leisure for his patients.

As an advocate for the mentally ill, he founded the Kirkbride Plan to improve medical care and standardize the buildings that housed patients. He firmly believed this architectural style would promote the recovery and healing of mental illness.

The shape of the building itself was supposed to have a healing effect—a special device to treat madness, improved and tastefully decorated. He was one of the pioneers of the American Psychiatric Association.

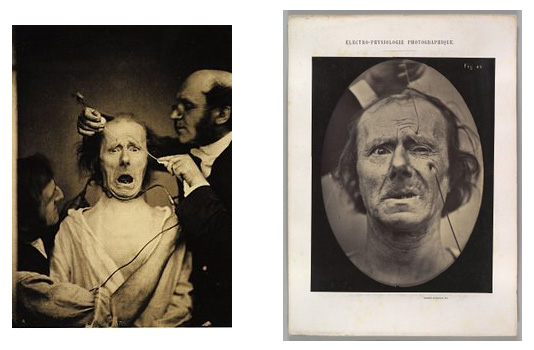

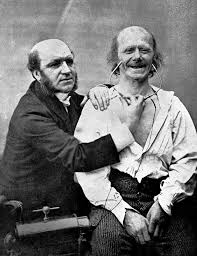

In 1844, Duchenne de Boulogne (1806-1875), a French doctor and clinical researcher considered a pioneer in neurology and medical photography, spoke about the utility of photographs in representations of the human face in his book The Electro-Physiological Analysis of the Expression of the Passions, Applicable to the Practice of the Plastic Arts. The photographic model for his pictures was a person with paralyzed facial muscles, so his expressions resulted from electrical stimulation.

![]()

His experiments led him to the conclusion that a true smile of happiness is formed by the muscles of the mouth and the eyes. This kind of smile is the so-called Duchenne Smile.

Charles Darwin included several of Duchenne’s photographs in his book, The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.

From then on, photography spread fast, arousing the interest of many amateur psychiatrists who documented physical changes associated with treatments.

In Spain, the earliest documents on the use of medical photography in Barcelona are preserved at the Instituto Frenopático de Les Corts, a psychiatric hospital founded in 1863 by Tomàs Dolsa i Ricart (1816-1909) and Pau Llorach i Malet (1839-1890).

In 1863, Dr. Tomàs Dolsa traveled to France to learn about the application of photography in psychiatry. Later, he wrote a document titled Photography as a Diagnostic Tool in Understanding Madness, in which he comments on a photography studio installation of which no graphic testimony remains: There is a magnificent photography workshop whose destiny will be the subject of a separate chapter.

Dolsa explains that the value of psychiatric drawing and photography was pointed out by Jean Etienne Dominique Esquirol (1772-1840), Joseph Guislain (1797-1860), M. Leurent, and Benoit Auguste Morel (1809-1873), who set up a photographic laboratory in Saint-Yon. Loret did the same in the Quatremares asylum.

It highlights the importance of photography as a diagnostic tool and comments on acquiring photographic equipment. The photography workshop at the Instituto Frenopático de Les Corts was apparently in full operation in 1882.

He also had an album with psychiatric photographs:

As a diagnostic tool to understand madness, the various positions, attitudes, and phases through which the clinical set of the alienated man passes, a practical examination through photography is perpetuated, and a complete album of specimens of different known nosological species is covered.

Photography was used as therapy in the Sant Boi asylum, founded in 1854. In 1892, Dr. Artur Galcerán Oranés (1850-1910) published El moderno Manicomio de San Baudilio de Llobregat, in which he stated the following:

Cattle farming and agriculture engage a large number of the asylum’s residents, especially during the harvest of grains, fruits, and flowers. Workshops have been opened for carpenters, cabinetmakers, painters, printers, bookbinders, foundry workers, blacksmiths, and tailors, and they also have a spice shop, a pharmacy, a grain depot, and a bookstore. (…) There are workshops for chromolithography and photography, and the remarkable works of this section deserve praise.

The medical photography by Catalan neurologist Lluís Barraquer i Roviralta (1855-1928), which is close to contemporary art, is interesting, not therapeutically but pedagogically.

He used several reproductions in his photographic archive for classes and lectures. His clinical photographs are usually high-quality. In many cases, we can appreciate the influence of Dr. Duchenne de Boulogne. Barraquer regularly worked with glass slides. At his death, he left a collection of about 2000 slides.

He used several reproductions in his photographic archive for classes and lectures. His clinical photographs are usually high-quality. In many cases, we can appreciate the influence of Dr. Duchenne de Boulogne. Barraquer regularly worked with glass slides. At his death, he left a collection of about 2000 slides.

Tomás Dolsa defines photography in medical settings, and referring to optics, he says:

It has offered us a series of lenses that can be immediately applied as living agents of the sense of sight. It has offered us the telescope, whose power to reach very long distances connects us with other worlds we wouldn’t know without its help. We have inherited the microscope, whose uses in medicine are well-known to all. In the anatomy section, a subdivision known as microscopic anatomy has been created: an instrument that significantly magnifies images of living bodies about other orders of bodies, both living and dead. We would strive in vain, or even the eyes of the keenest observer would strive to discern them. Nevertheless, optics has remarkably expanded the sphere of human activity, and since humans are intelligent, they never tire of broadening their useful applications more and more each day. Photography is one of them. Photography is, therefore, the art of fixing, through the chemical action of light, the image of external objects. (…)

Why, then, should alienist physicians, who have drawn the characteristic elements of their patients’ ailments in their physiognomy, not be regarded as painters, sculptors, and photographers who immortalize in their offices the series of morbid representations that become so clear during the course of the illness? The alienist physician shouldn’t be indifferent, and the method of investigation that we follow, advise, or recommend is extremely useful to them.

Since we are talking about physiognomy, what is physiognomy? The physical and physiological representations visible by simple inspection indicate the many moral, intellectual, and emotional representations of man. ‘Physiognomy is the man’ (Buffon). It has also been called the ‘mirror of the soul.’ It is a mobile result of particular expressions; as indicated in the definition, it reflects the various phases of intelligence, feelings, instincts, vices and virtues, and characters. To demonstrate the deep interest that should inspire alienists, if we were to do a historical review of those who have dedicated themselves to this part, we would see that even Hippocrates assigned significant importance to the study of the face. His most illustrious successors have imitated this study, including Ariosto, Adamansio, Molier, Lavater, Porta, Curdan, Levi, Lachambra, Lepeletier, and many others. Mental health care cannot overlook or disregard photography as a diagnostic tool. In madness, the disruption of the physiognomy often takes exaggerated forms and proportions, presenting, depending on the nature of the intellectual disturbance, the most bizarre aspects, marked contrasts, or surprising concentration or mobility. These have been observed and continue to be observed in patients, and to ensure they are never erased from the observer’s memory, photography is employed to reproduce them. (…)

Our institute already has a machine for this purpose, which will not take long to start operating. We envision it as a new source of satisfaction and benefit for science and humanity.

DOLSA, circa 1863, PHOTOGRAPHY as a diagnostic tool in the knowledge of madness.

The use of photography as a therapeutic tool was explored and investigated by many doctors and psychiatrists with different individual and group techniques and resources:

- Self-recognition and self-image.

- Reaction and emotions expressed in response to images.

- Discussions.

- Projective purposes.

Therapeutic techniques used in photography rely on and prioritize the analysis of personal snapshots and family albums, then shift this focus to the creative act itself as a means of constructing personal narratives.

This concludes the first part of this fascinating story.

You can continue with the second part, where you will find experiences from the 20th century to the present day. I’d gladly receive all your comments and contributions to this entry.

I also invite you to explore the: