Wickedness is in the eye of the beholder.

Nan Goldin

If your worst fear took a human form, what would it look like?

Working with fear through photography is a creative task. Photographing what worries you or projecting onto other images has great power in mobilizing emotions.

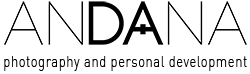

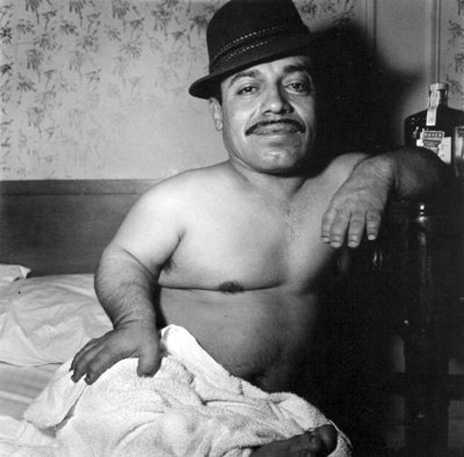

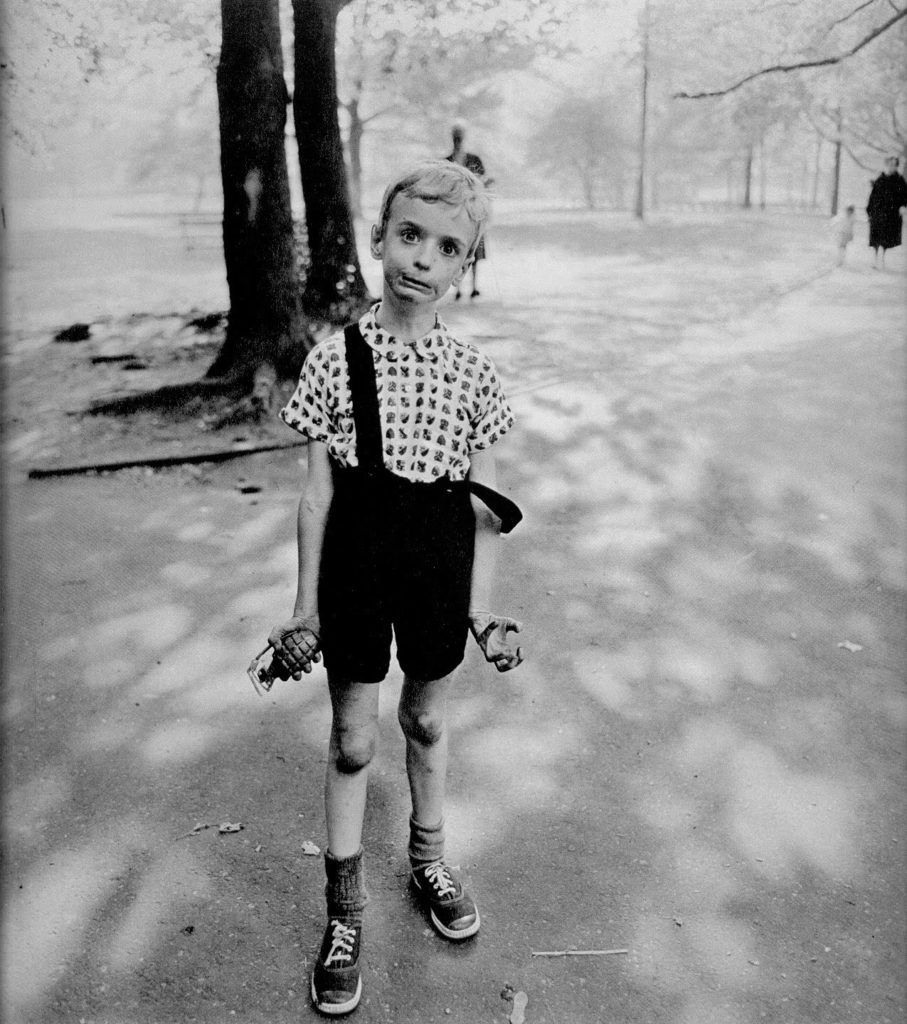

Diane Arbus took photos of individuals on the street, not the conventionally beautiful or fashionable, but rather those who were different and sparked curiosity and intrigue, those who were deemed strange. She was curious about anomalous and marginalized people. Only she dared catch their gaze, expression, lights, and shadows.

Diane’s parents worked at a prominent and profitable fashion store, Russek’s. Her father, David Nemerov, served as the company’s vice president and was responsible for window displays and setting winter coat trends. Diane was born in a wealthy New York environment in 1923 and was the second of three children. With a father who spent his days working and a depressed mother, she was raised by nannies and educated in prestigious schools for the wealthy.

This family environment, possibly lacking in affection, may have influenced her to rapidly fall in love and leave home, leading her to marry Allan Arbus at 18.

Together, they founded the photography studio Diane & Allan Arbus, working for clients such as Russek’s, Glamour, and Harper’s Bazaar. Their work was a true collaboration, with each of them proudly highlighting the other’s strengths—they were a team.

Diane had a passion for documentary photography and often wandered alone through nightclubs, where she began her first personal projects.

After separating from her husband, Diane decided to devote herself completely to her passion. She studied photography under some of the best of her time: Berenice Abbott, Robert Frank, Louis Faurer, Brassaï, Weegee, and, above all, Lisette Model, who advised her, “Never photograph something you are not passionate about.”

Diane and Lisette shared a friendship and many things in common. Lisette approached poverty, misery, and old age with a humanistic perspective, while Diane captured the essence of strangeness and the abnormal in her photography. She was fascinated by twins, strange couples, blind people, albinos, deformed people, and grotesque faces… Lisette was her great mentor, encouraging her to photograph subjects that could evoke pain and cultivate an impeccable technique.

Diane was attracted to the abnormal: nightmares, survival, and what society refused to see. Her unique way of looking at and photographing her subjects set her apart from other photographers working on similar themes.

Diane Arbus had no fixed moral or artistic rules. She disliked social masks and aimed to coax her subjects into shedding them, aspiring to show them as they truly were. This led to society misunderstanding her work.

She was methodical, preparing her projects in series. Taking a photo was a process, a prior adventure. Diane approached others with genuine interest and passion, often chatting with them for hours, sharing moments, and earning their trust. She never mocked them; instead, she engaged with them, listening intently as they shared their secrets.

Arbus tapped into the Gestalt precept that we all enjoy being looked at, and in that sense, the camera is the perfect medium to encourage the exhibitionist spirit. After looking at them with all her senses, she took advantage of this to photograph everyone she was interested in. People with whom almost no one spoke felt cared for and showed her their best pose.

Diane Arbus is a clear example of how art is intertwined with personal history, family dynamics, unresolved issues, parental influences, and one’s perception of life. The key to Diane’s photos is in her childhood. As a child, she was forbidden to look at the abnormal. Through her photographs, she confronted her fears—the night terrors instilled by babysitters to keep her quiet, the silence, and the absence.

There are varied opinions on Diane Arbus’s approach and ethics, but from my perspective, Diane was working through her terrors. For her, the photographic process was an adventure—a personal journey to test her courage, exorcise her demons, and reclaim her childhood sense of loneliness in order to confront the monster and rob it of its power to frighten her.

In 1971, at the most successful stage of her life, Diane committed suicide at the age of 48.

Many questions remain.

Diane Arbus was the first photographer to be included in the Venice Biennale. Today, she remains a reference and a profound influence. Her impact transcends generations and has repercussions on the work of other creators such as Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Gillian Wearing.

Looking at a photograph by Diane Arbus means seeing with the eyes of empathy, allowing the initial horror or ugliness to fade, and perceiving what lies beyond: the humanity of the person portrayed and recognizing oneself in the photographer. These photographs invite deep reflection on concepts like normalcy, privacy, beauty, and love.

My dear, I wonder if before the end

You ever thought about a children’s game—

I’m sure you must have played it too—in which

You run along a narrow garden wall

Pretending it’s a mountain ledge, and try

Not to fall. I wonder if you fell, and thought

For the first time,

This is what it means to die

Because life’s failed you, or you failed in life,

As other children sometimes feel when they

Let go their mother’s hand, are lost a while

Among strangers, and think,

This is what it means

To be alone. That was long ago. The game

Was always dangerous, and now you’re gone,

No way to stop or move aside, as one

Who, turning to avoid an obstacle,

Sees there before him the way the world will end.

I wonder if you were afraid as well

To play the game, or only tired of playing,

And in either case, whether you jumped or fell.

Howard Nemerow

Diane Arbus’s brother

Keep researching this exciting photographer. We would love to hear your thoughts on photography and fears and any comments this post inspires. Feel free to share your views in the comments section.