If there are significant artists who use photography as a tool for self-exploration and personal growth, one of the most important is Claude Cahun. If you aren’t familiar with her, I encourage you to explore her work, as it deserves to be recognized and remembered.

In the mid-1980s, French writer François Leperlier found photographs signed by Claude Cahun while researching a book on surrealism. At first, he believed Claude Cahun was a man until he realized she was a woman. He showcased her work, establishing her as a key figure in the history of photography.

The first known self-portrait of Cahun. 1912.

The first known self-portrait of Cahun. 1912.

Feminine in appearance, with long hair and painted lips.

Lucie Renee Mathilde Schwob was a photographer, writer, sculptor, actress, and critic. At one point in her life, she decided to call herselfClaude Cahun.

Born in Nantes, France, in 1894, she was surrounded by writers and publishers in her bourgeois childhood. Her mother had a mental disorder, so her maternal grandmother raised her. At 15, she met her lifelong companion, Suzanne Malherbe. They fell in love and remained together for the rest of their lives. At 18, she took photos.

In 1919, she likely began exploring her identity by adopting a new name. She chose an androgynous name, one that could be used by both men and women: Claude. She adopted her maternal grandmother’s last name, Cahun, to preserve her connection to the women in her family, especially the woman who raised her. In this way, she created a new name for herself: Claude Cahun. Her partner, Suzanne, also changed her name to Marcel Moore.

Interestingly, Claude’s father married Suzanne’s mother; both were widowers. Thus, at 23, the two women were lovers and stepsisters. They settled in Paris, worked together, and collaborated on each other’s projects.

Claude Cahun, self-portrait, 1929.

She was a highly versatile artist, drawn to all forms of art. She wrote, painted, made collages, and worked as an actress, portraying both female and male roles. In 1925, she created her series Héroïnes, using self-portraits to transform herself into figures like Sapho, Pénélope, Salomé, Eve, Dalila, Judith, and Hélène—female archetypes. Around 1929, the magazine Bifour published her Anamorphic Self-Portrait.

Claude Cahun defined herself sexually as gender neutral. As a man, she appeared very feminine; as a woman, she was very masculine. The ambiguity was part of the mystery and depth of her photographs.

She was a surrealist artist who used photomontage and performance to create dreamlike and alternative realities.

Claude Cahun, Que me veux-tu?, 1928.

Her work was fundamentally rooted in self-portraiture and the exploration of personal identity. She was interested in androgyny, taking pictures and writing about it. She was connected to avant-garde movements and active in the surrealist movement, but she faced discrimination for being a woman and because of her sexual orientation. As a result, she was never allowed to become an official member of the surrealist movement.

Claude Cahun, Self-portrait, 1927

When Claude Cahun chose to transform into Clara Bow, the American actress who starred in the film “It” (Clarence G. Badger, 1927), it was intriguing. “It,” translated as “That,” refers to a quality of the mind or a physical attraction with strong magnetism that draws both sexes.

It is not necessarily beauty, so to speak, nor good talk. It’s just “that.”

Rudyard Kipling

That (It), that strange magnetism that attracts both sexes…

Elinor Glyn

Cahun, wearing Clara Bow-style makeup, writes, “I am in training. Don’t kiss me” across her chest, complete with fake nipples. Her playful, effeminate expression and pose later evolve into another photographic series. The hair gel and makeup disappear, replaced by traditionally masculine gestures and poses.

Claude Cahun, Autorretrato. 1929

These photographs invite us to reflect on the societal consensus surrounding gender identity—perspectives that conceal power structures and deny the complexity and richness of human nature. The artist uses photography to address this issue, revealing the polarity and artificiality of gender roles.

In this way, Claude Cahun’s entire body of work challenges the concepts of identity, being, and gender—presenting them as masks. These fluid ideas are continually recreated and reinvented as needed.

The photographer expanded on A. Rimbaud’s message, “Je suis autre” (I am another), saying, “Je suis autre, un multiple toujours,” meaning “I am another, always a multiple.”

Me as Cahun Holding a Mask of My Face by Gillian Wearing, 2012

Cahun inspires. In 2012, Gillian Wearing, a British artist who works with the concept of identity, paid homage to her with her photograph “Me as Cahun, Holding a Mask of My Face.”

The work of Claude Cahun transgresses gender boundaries. It is self-represented in feminine, masculine, and androgynous forms. She poses aggressively, seductively, and demurely. Cahun defies all attempts to categorize her gender according to the binary notion of man-woman or male-female. On the contrary, she creates her own category, where she is free to express herself according to her own desire.

Melissa Huang

Claude Cahun reinterprets herself permanently; she is unique and multiple. Her photographs show the same eyes and the same body; everything else is constructed. The artist aims to convey the following: identity is ever-changing, adapting to the theater of life, constantly constructing and deconstructing itself. Being, gender, and sexuality are masks we can shape at our will. We are fluid and adaptable.

The artist defined her sexuality as neutral, neither male nor female, but both. She shaves her head to be only a body without masks. It is the viewers who, once again, assign an identity to how she looks, shaped by our culture, beliefs, and prejudices.

In 1937, the couple fled fascism and settled in Jersey, posing as sisters. There, they created anti-fascist propaganda signed by the “anonymous soldier”—acts of resistance that became part of their artistic expression, blending revolution, aesthetics, and transgression.

Self-portrait by Claude Cahun, 1945

![]()

For four years, the couple managed to distribute 4,000 anti-Nazi leaflets in their guerrilla practices. In 1944, the Gestapo caught Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore. The Nazis were humiliated when they discovered that two Jewish women had undermined the morale of their troops. They were imprisoned, and at the end of the war, Claude died at the age of 60 in 1954.

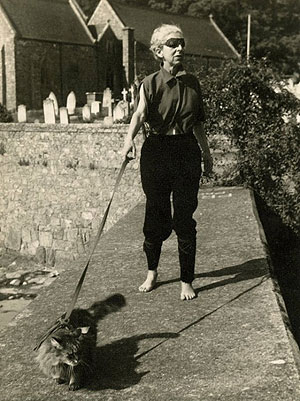

Marcel Moore could never overcome the loss of her great love, Claude Cahun. She committed suicide 20 years later. Both are buried together at St Brelade’s Church in St Helier, Jersey.

Around 1948, she worked on her final self-portraits in a series titled The Way of the Cats. As a great lover of this animal, I find it fascinating and relatable that this artist photographed herself with her cats on multiple occasions, using them as a symbol of freedom.

Claude Cahun. Lucie and kid. 1926

Claude Cahun. Le chemin des chats. 1949

Claude was an artist who explored the idea of identity and gender, pioneering more current feminist thoughts.

Today, Claude Cahun reminds us that what makes us unique is the freedom to choose who we want to be in every place and at every moment of our lives. Claude Cahun used self-portraits to document transformations, invent possible identities, and become whatever she desired.

The camera not only captures who we are but also allows us to invent who we want to be. It reveals that our identity is fluid and ever-changing. We have the freedom to reinvent ourselves at any moment of our lives, and that is aprofound form of liberation.

I close my eyes to delimit the orgy. There’s too much of everything. I better be quiet. I hold my breath. I curl up, abandon my boundaries, and retreat toward an imaginary center… not without premeditation. I have my hair shaved, my teeth and breasts torn out—everything that irritates or unsettles my gaze—my stomach, ovaries, and even my conscious, cystic brain.

When I’m left with only a card in my hand and a heartbeat to

feel, but with perfection, I will, of course, win the game.

Claude Cahun

.

If we use photography in our daily lives while understanding it as a tool for memory, art, and the construction of identity, we may become more responsible for the images we create. Only in this way will they be the tool to change the world.

If you want, you can continue reading: The Origin of Photography as a Tool in Mental Health. Part one.

Thank you for being here.