Documentary photography is a powerful tool for social representation, but it also raises ethical dilemmas related to the gaze, vulnerability, and the construction of narratives about others.

From a psychological perspective, this article explores the cognitive, emotional, and relational processes involved in the act of photographing, with the aim of encouraging more respectful, conscious, and collaborative practices in today’s visual culture. The proliferation of images in contemporary society has heightened the importance of psychologically analyzing the act of looking.

Some photography exhibitions move me deeply, while others make me feel profoundly uncomfortable. The World Press Photo has always fallen into the latter category. Not because I question the value of photojournalism, but because certain images awaken an intimate, almost physical conflict in me: a knot in my stomach, a lingering unease that stays with me long after leaving the exhibition room.

This kind of work reveals the emotional and cognitive impact that certain documentary images can have, provoking responses ranging from empathy to moral discomfort.

Far from questioning the value of photojournalism, this text proposes a critical review of how we construct meaning when we observe —or produce— images of realities that are not our own.

Representing the Other: A Psychological and Ethical Process

This feeling of discomfort arises especially when I see images that tell stories of lives that do not belong to the person behind the camera. Photographs taken in distant countries by people even more distant; intimate stories told from the outside, without being part of them. That’s where a hard-to-explain sensation arises: the impression of entering a reality that doesn’t belong to me, of witnessing something fragile from a distance that never feels truly innocent.

Given my background, I can’t help but view documentary photography as a space of relationships: relationships of power, of representation, of interpretation and, above all, of responsibility.

Social and cultural psychology have extensively described the processes through which we interpret others based on our own cognitive and emotional frameworks. Documentary photography, by capturing a moment and turning it into a visual narrative, can amplify these mechanisms. The processes involved include:

- Inference and stereotyping: the image facilitates cognitive shortcuts that reduce the complexity of human experience.

- Ethical distance: the viewer relates to suffering from a position of no direct involvement, which can reduce their perceived responsibility.

- Relational asymmetry: the photographer holds agency; the person portrayed does not always have it.

These dynamics place the photographer in a position of symbolic power that should be questioned. The camera, far from being a neutral tool, constructs meaning. And in that act of construction and looking —between fascination and discomfort— ethical questions arise that we cannot avoid.

To what extent can the camera tell a story without appropriating it, without colonizing, reconstructing or adapting it —without turning it into something that no longer belongs to the one who lived it, but to the one who looks at it?

When a story is told by someone outside of its context, a phenomenon that social psychology has studied extensively is triggered: the representation of the other through an external framework, where categories, meanings, and emotions are interpreted by the observer, not the person experiencing them..

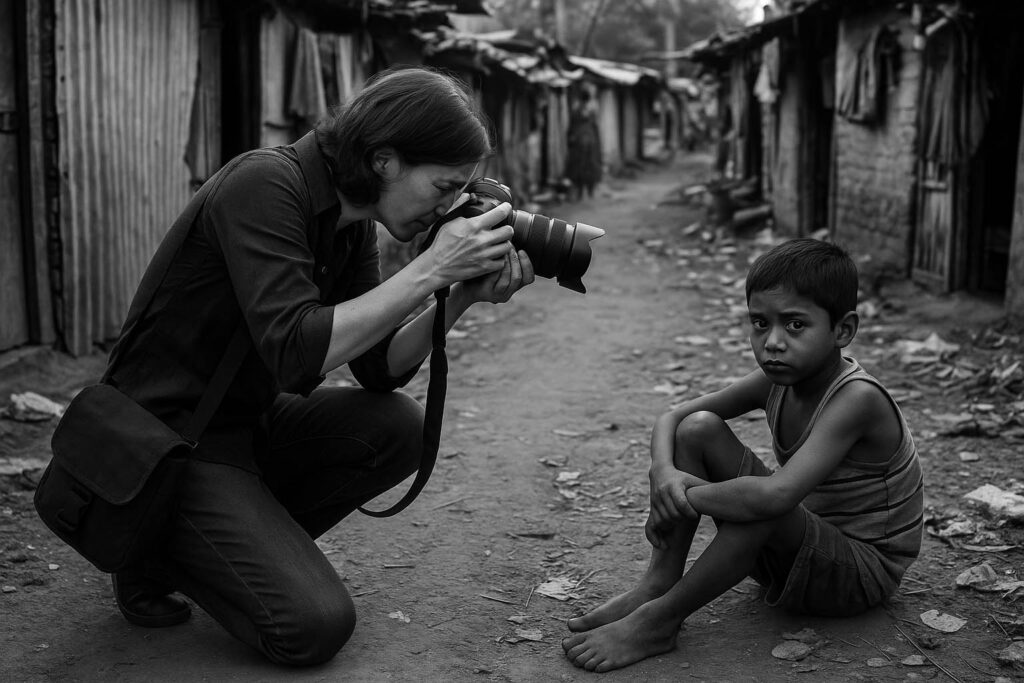

Image created with Google Gemini using the following prompt: We’ve just published a new blog post — this one: https://andanafoto.com/en/documentary-photography-and-the-responsibility-of-looking/ Please create an image that represents it.

Some images hurt unintentionally —or deliberately. Perhaps that’s why the aesthetics of mockery or pain unsettles me so much, as it’s so present in some documentary work. Images that aim for quick impact, that freeze a person in their most vulnerable moment, that showcase the wound.

That aesthetic —sometimes unconscious— turns reality into spectacle. And without realizing it, turns someone into an object rather than recognizing them as a subject.

An image does not merely describe: it condenses, selects, emphasizes, and at times, oversimplifies.

The person photographed is pinned to a single gesture, a single moment, which can unintentionally become their public identity. What is a visual narrative for the photographer may be a form of reduction or stereotyping for the person portrayed.

Psychology knows that humans are particularly vulnerable to such simplifications. The brain interprets using cognitive shortcuts: it sees a face, a wound, or an expression of pain, and instantly builds a narrative. That’s why the image holds so much power… and so much responsibility.

And yes, of course it’s necessary to make visible the realities, the social injustices, the wars, the cities, and personal transformations… but the inevitable question is: from where? Can we photograph without invading?

To photograph means to interpret, to choose, to frame… but it also means to take a stance. And that’s where the ethical tension arises:

What right does someone have to tell a story that is not their own?

Is the story being accompanied or is the subject being used?

Is it being looked at or taken?

I wonder how we can address this discomfort in the 21st century and not contribute to social anesthesia from an ethical standpoint.

What questions could accompany those who look through the camera?

Perhaps asking them before creating the image could guide us toward a more ethical path.

- Do we photograph to understand or to make an impact? Intention always shows in the image. What are we really seeking: to understand or to impress? It can’t be both.

- To accompany or to exhibit? Are we standing beside the person or using them as a symbol of something?

- So the person or the issue can be seen, or so the photographer can gain recognition through them?That might be the most uncomfortable question… and the most necessary one.

There are alternatives, more respectful paths: Participatory methodologies developed in community psychology, education, and anthropology offer more equitable models for image production. Among them are:

- Participatory photography (Photovoice): allows communities to represent their own narratives.

- Co-authorship processes: the photographer acts as a facilitator, not the main interpreter.

- Dialogic construction of the narrative: decisions are made collaboratively, reducing asymmetry.

These approaches redistribute the power of the gaze and promote an ethic based on agency, dignity, and the recognition of the other as an active subject.

To me, 21st-century documentary photography should be educational and place the camera in the hands of those who can tell the story from within.

Documentary photography in the 21st century can become an educational and transformative space if it stops focusing solely on looking at the other and begins to ask how to look with the other.

When photography is placed within this framework, it ceases to be a tool of extraction and becomes a tool for encounter, agency, and dignity.

And perhaps, deep down, that’s what many of us are searching for: to look without harming, to document without appropriating, to tell without erasing the other.

These ideas arise from a personal experience, but also from a professional concern: how we construct the gaze in a society saturated with images, and what psychological, social, and ethical effects this construction has.

I do not write to assign blame or to discredit an essential discipline. The contemporary challenge is to look without harming, to narrate without appropriating, and to document without silencing the other’s voice. Only through doubt, critical analysis, and dialogue can we foster photographic practices that promote narrative justice and human sensitivity.

If this text stirred something within you, perhaps that’s already the most important part of this reflection —I’d love to hear about it.

Note on the Images in This Article

To accompany this article, we chose to include images generated with Artificial Intelligence based solely on the content you’ve just read. In addition to the one you’ve already seen, here are the other two created by ChatGPT.

The result can be unsettling: these are photographs that are not real, even if they appear to be. The difference is essential, but not always obvious. These two synthetic images convey the same pain, the same aesthetic, and the same emotional narrative… yet they do not stem from any real event nor do they depict any existing person.

The result can be unsettling: these are photographs that are not real, even if they appear to be. The difference is essential, but not always obvious. These two synthetic images convey the same pain, the same aesthetic, and the same emotional narrative… yet they do not stem from any real event nor do they depict any existing person.

References

Barthes, R. (1981). Camera lucida: Reflections on photography. Hill & Wang.

Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed.). Continuum.

Harper, D. (2002). Talking about pictures: A case for photo elicitation. Visual Studies, 17(1), 13–26. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14725860220137345

Sontag, S. (2003). Regarding the pain of others. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Wang, C., & Burris, M. A. (1997). Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Education & Behavior, 24(3), 369–387. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/9158980/

Cómo citar este artículo

Al citar, reconoces el trabajo original, evitas problemas de plagio y permites acceder a las fuentes originales para obtener más información o verificar datos. Asegúrate siempre de dar crédito y de citar de forma adecuada.

How to cite this article

By citing an article, you acknowledge the original work, avoid plagiarism issues, and allow access to the original sources for further information or data verification. Make sure to always give credit and cite appropriately.

Amparo Muñoz Morellà. (December 10, 2025). "Documentary Photography and the Responsibility of Looking". ANDANAfoto.com. | https://andanafoto.com/en/documentary-photography-and-the-responsibility-of-looking/.